The word “homeless” is imprecise.

A homeless person could be living on the street, in a shelter, or in their car. They might be seriously mentally ill, or just between jobs; on the streets for a month, or the last twenty years. All we know is that they don’t have a permanent place to stay, and probably want one.

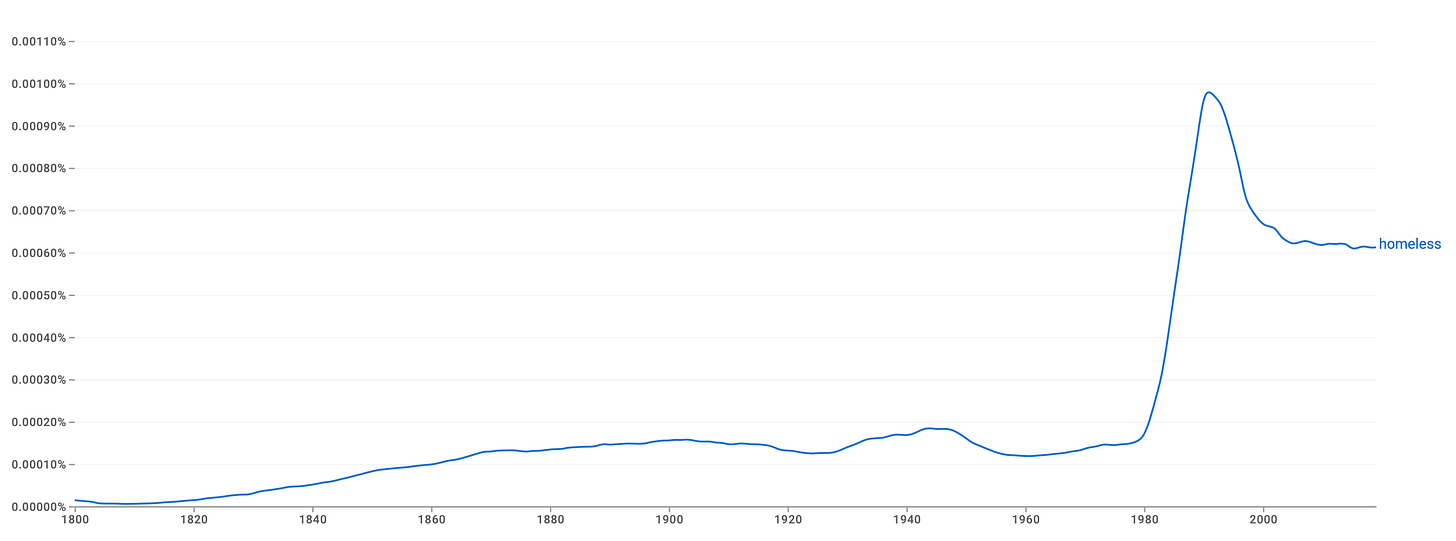

We take for granted that a class of “homeless” people exists, defined by their lack of housing. But the term “homeless” is actually a pretty recent one, and we use it today because it was popularized by activists in the 1980s.

In a recent talk at the Manhattan Institute, Stephen Eide explains how the language of homelessness evolved over time. In the 19th century, people talked about the “wandering poor” or “placeless men” who moved across the country on newly built railways to work. A “Tramp” counterculture developed, similar to Beat or Hippy culture, with its own vocabulary: “hobos” moved around and worked; “tramps” moved around and lived off of their wits; and “bums” were retired or disabled hobos and tramps. Homelessness was a lifestyle choice, and those practicing it were fiercely proud of it:

In the early twentieth century, a hobo insisted that his was a lifestyle choice. He wanted to be on the road. He exemplified in his mind, and also in people like Jack London’s mind, the best of America: rugged individualism… A hobo was proud to be a hobo.

In the early 20th century, changes to the labor market and New Deal policies like unemployment insurance made it more economical for workers to stay in one place instead of moving around for jobs. The hobo and tramp gradually disappeared, leaving only the bums, who tended to be older alcoholics. A number of “skid row” neighborhoods developed in big cities where the bums could live in cheap single-occupancy hotels.

Once cities and developers decided to put the land to better use, the bums were kicked out and started living in train stations, subways, parks, and plazas. In the 60s and 70s, they were joined by people with severe mental illnesses who were being let out of mental institutions. The homeless transitioned in the public conscience from rugged individualists to victims of “the system,” and it became politically incorrect to use terms like bum, vagrant, or derelict.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that organizations centered around “homelessness” began popping up across America. Activists wanted this population to be called “the homeless” because the name contained an obvious policy directive – give homeless people homes. This rebranding has been quite politically successful: billions of dollars have since been spent on housing first policies, and it is now taboo in mainstream policy circles to suggest that other problems the homeless face, like unemployment and addiction, are due to their own poor choices or moral failings rather than being homeless.

Today the same class of activists who popularized the term homeless are moving away from it and towards clunky phrases like “people experiencing homelessness,” “the unhoused,” and “residents without addresses.” It’s a classic case of the euphemism treadmill, in which a term (homeless) used to replace a politically incorrect word (bum, vagrant, derelict), becomes offensive by association with the very concept it describes (the kinds of people unable to house themselves). These changes, Eide sardonically reminds us, do nothing to fix the basic problem with the term homeless, which is its imprecision:

This term groups victims of domestic violence, ex-offenders leaving prison, people with untreated schizophrenia who decades ago would have been institutionalized, people addicted to fentanyl and meth on the streets of the Tenderloin… Very different problems. We’re going to need to do very different things to help these people. But what’s the most important thing to know about these people? They’re all homeless.

If lack of housing were the real root problem then homelessness would have been solved a long time ago.