Mental Health Credentialism Costs Lives

The case for a quicker route to becoming a psychiatrist, psychologist, or therapist

There’s a cost-effective and practical way to improve mental health care, and that’s by shortening the time it takes to become a psychiatrist, psychologist, or psychotherapist and letting them do more to treat mental illness.

I’m not saying there shouldn’t be any standards whatsoever. The mentally ill are a vulnerable population, and there should be barriers to protect them from incompetent or malevolent actors. But the current situation doesn’t make sense.

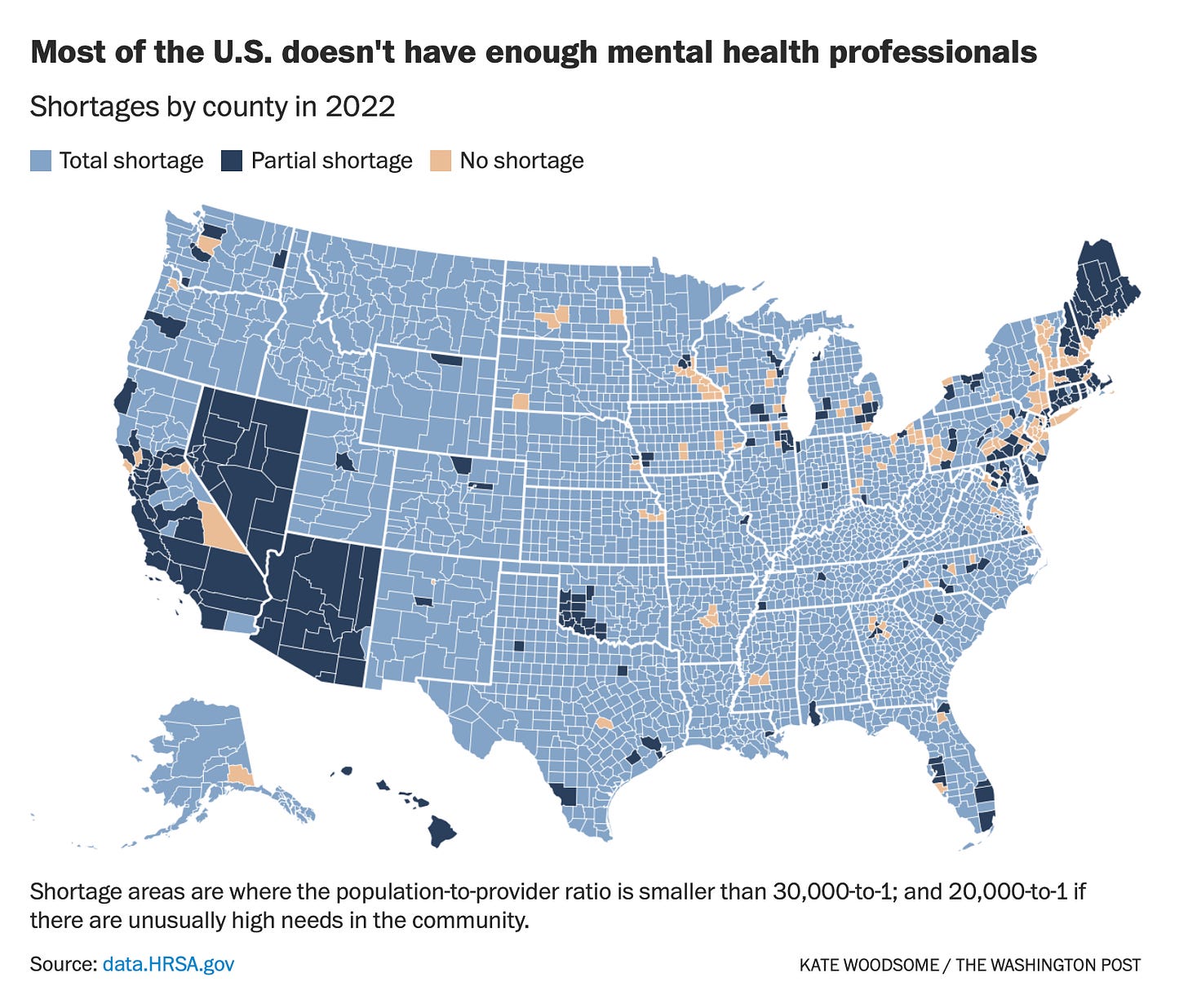

The United States is experiencing a psychiatrist shortage, with patients in rural areas and poorer urban settings most lacking access. While the conversation around addressing this shortage has mainly focused on how to persuade medical students to enter psychiatry, we should be discussing whether it makes sense for would-be psychiatrists to go through 12 years of education and training in the first place. Clinical psychologists are also in short supply, with 56% no longer taking new patients. It takes between 9 and 12 years to become one.

The lengthy path to completing these advanced degrees is a historical accident more than anything else. Psychiatry originated within the field of medicine, which is why psychiatrists must study to be physicians even though they end up treating mental illnesses. After World War II, there was a shortage of psychiatrists to care for returning soldiers with mental health problems, so psychology PhDs were permitted to step in and provide treatment, birthing the field of clinical psychology.

While there is a lot to learn about the science of mental illness and its treatment, it shouldn’t take longer to become a psychologist or psychiatrist than to become a lawyer, civil engineer, or military officer. Representing a defendant in criminal court, designing a bridge that millions of cars will drive over, or making life-and-death decisions on the battlefield involve risks that are at least comparable to the most critical decisions in mental healthcare, such as whether to involuntarily hospitalize a patient. Shortening the length of these programs or allowing people to start them as undergraduates would lead to more people entering and completing them. This is especially true for clinical psychology, which takes a similar amount of time to complete as psychiatry but pays less than half as much.

A master’s degree in counseling, social work, or psychotherapy is typically required to be a psychotherapist. Yet therapists with more education or training do not have significantly better client outcomes, and different psychotherapies are similarly effective at treating common mental health conditions. Given that the most robust predictor of success in therapy is the quality of the relationship between therapist and client rather than the therapist’s expertise in academic psychology or the specific type of therapy they are trained in, it would be sensible to scale back the educational requirements to become a therapist.

One could agree with my previous points and still support current educational and training requirements because of the selection effects they create. Lengthy and competitive processes filter out individuals who are less competent or dedicated, and the differences in time it takes to complete different degrees loosely correspond with a hierarchy of knowledge and skill. Additionally, the time it takes means that psychiatrists and psychologists tend to be older when they begin practicing, and in mental healthcare there's generally a preference for older and wiser professionals relative to fields like law or engineering.

All that said, there’s likely a sweet spot we’re overshooting. Many caring and intelligent people avoid these careers because they don’t want to be a student for a decade, and while longer educational requirements may bump up the average age of skilled clinicians, it also deters middle-aged people looking for a second career from switching in.

Finally, there are laws that regulate what treatments and services different kinds of mental health professionals can provide. For instance, psychologists can administer psychotherapy and conduct psychological testing but not prescribe medication in most states. While these regulations exist to protect patients, relaxing them may save lives. States that have granted psychologists with psychopharmacological training the ability to prescribe psychiatric drugs have seen a 2% increase in the number of children receiving mental health medication and a 5 to 7% drop in suicides compared to states in which psychologists cannot prescribe.

Here are some suggestions for how we could lower the amount of time it takes to become a mental healthcare professional while keeping standards high:

Let aspiring psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and psychotherapists begin their specialized training during undergraduate studies.

Offer undergraduate programs in psychiatry and clinical psychology with direct pathways into these advanced degrees.

Create an alternative medical school curriculum for people who want to be psychiatrists with a greater emphasis on psychopathology, neurobiology, and psychopharmacology.

Allow undergraduate psychology programs to offer a pathway to become a registered psychotherapist, such that graduates who complete the requisite coursework and practicum can practice once they graduate.

Enable psychologists with appropriate psychopharmacological training to prescribe psychiatric medications in all states, following the model of states that have already implemented this.

Maintain high student standards by continuing with standardized tests, comprehensive exams, and challenging practicums.

I’m not advocating for anything radical here. I still think mental health professionals should be educated, trained, and supervised for a time. But more people want mental health care than ever before, and there simply aren’t enough licensed professionals to treat everyone right now. Wait times are long, and people with the worst mental illnesses often have access to the least amount of care. All we have to do is cut down on the amount of time mental health professionals spend in school and expand their capabilities by a reasonable amount, and the supply of mental health care professionals would rise to match the growing demand.

I totally get where you're coming from and I agree we need to think about novel solutions to the problem, but I think there may be some issues with your proposals.

"1. Let aspiring psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and psychotherapists begin their specialized training during undergraduate studies."

I'm all in favor of medical training starting earlier, but I don't see a reason to limit this to mental health. If we're already making the changes you're proposing, we might as well make it easier to start medical school earlier, eg. by combining undergrad and medical school into a 6 year program or something like that, which I think some places already do.

"2. Offer undergraduate programs in psychiatry and clinical psychology with direct pathways into these advanced degrees.

3. Create an alternative medical school curriculum for people who want to be psychiatrists with a greater emphasis on psychopathology, neurobiology, and psychopharmacology."

Would this be an entirely separate school? Or would it be some kind of sub-curriculum within existing medical schools? If it is a separate school, how will trainees get appropriate exposure to sick & hospitalized patients, and how will they learn to work with their medical colleagues? Distancing psychiatry from the rest of medicine seems like a bad idea and will likely lead to problems similar to what the psychoanalytic community faced when it self-segregated from the broader medical/psychiatric institutions.

If it is a sub-curriculum within medical school, why should psychiatry be the only field that's so different? Wouldn't it then just make sense to completely revamp medical school and allow people to start studying psychiatry, orthopedics, radiology, or whatever else in undergrad? Also, if it is a sub-curriculum, remember that trainees in psychiatry still need to do rotations on all the other medical specialties during medical school, just like medical students who go into ophthalmology still need to rotate through OBGYN and psychiatry, etc. A huge part of medical education is not just learning your own specialty, but learning how all of it fits together, which means spending lots of time learning from other fields.

For psychologists, I guess we could experiment with 6 year combined undergrad-graduate programs, kind of like a BA and s PsyD degree combined. Maybe there's already some of those, I'm not sure. But again, something like that would mean med prescribing and having a heavy medically-oriented practice would be harder since those 6 years really aren't enough to become proficient in this stuff. Psychology programs can claim they teach pharmacology and other courses "necessary" to become proficient in prescribing medications, but without the broader medical education it still isn't enough training.

"4. Allow undergraduate psychology programs to offer a pathway to become a registered psychotherapist, such that graduates who complete the requisite coursework and practicum can practice once they graduate."

I don't think 22 year old college graduates are ready to be psychotherapists, for the most part.

"5. Enable psychologists with appropriate psychopharmacological training to prescribe psychiatric medications in all states, following the model of states that have already implemented this."

I think this will turn out badly. Learning to prescribe medication well is not easy, and everything I've seen re: psychologists, APNs, and other mid-level providers prescribing psychiatric medications has convinced me that they are not qualified to do it and the training is woefully inadequate. If anything, people need way more training, or at least better quality training.

"6. Maintain high student standards by continuing with standardized tests, comprehensive exams, and challenging practicums."

Obviously I'm in favor of high standards, but actually implementing them is difficult. Separating psychological/psychiatric training further from the medical establishment will make this goal more difficult and probably undermine it. Even within the medical establishment, we have tests and credentialing up the wazoo but it isn't clear we're getting better.

re: length of training, on the one hand I agree the time it takes to become a physician is long, but on the other hand it's not clear that more than 2 years can be cut out and still have the training be robust enough. Maybe 3 years if you're being ruthless and you know the caliber of your incoming students is high (which will be less likely if we're opening the doors for far more people to enter the profession). But once you've created combined 6 year college-med school programs, it's not clear what else you could cut out.

I think medical school could be shortened to 3 years if we're really smart about it, perhaps collapsing the 4th year into the 1st year of residency. But eventually we're going to run into the problem of having too many graduates who are inadequately trained and probably not mature enough for some parts of the job. To some extent, having a long training period and lengthy selection process may be a necessary evil.

Nice POV! I appreciate this conversation. Social worker here. The lack of representation at the national level means we're excluded from this conversation and have the disturbing outcomes of the helping professions. Our foundation being systems theory and person in environment places us in the right position to be leading these conversations. We center the client and their needs at a macro, mezzo, and micro level. More than other professions, we work with people who otherwise don't have access to psychiatrist and psychologists.

But, there's no clear definition of what we do and social work standards aren't nationalized in a way that creates parity across states despite having the same educational requirements. And let's not even get into money. Our degrees are ridiculously expensive and then requires a minimum of 3 years practicing clinical social work before taking an exam, to make how much? Social workers on average make $20,000 less than nurses.

No real solution to the mental health crisis can be taking seriously without addressing the current barriers to social workers having a descent life while carrying the heavy load of working with and for the most needed.