A paper on the economics of mental illness was recently published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Here’s the abstract:

Mental illnesses affect roughly 20 percent of the US population. Like other health conditions, mental illnesses impose costs on individuals; they also generate costs that extend to family members and the larger society. Care for mental illnesses has evolved quite differently from the rest of health care sector. While medical care in general has seen major advances in the technology of treatment this has not been the case to the same extent for the treatment of mental illnesses. Relative to other illnesses, the cost of care for mental illnesses has grown more slowly and the social cost of illness has grown more rapidly. In this essay we offer evidence about the forces underpinning these patterns and emphasize the challenges stemming from the heterogeneity of mental illnesses. We examine institutions and rationing mechanisms that affect the ability to make appropriate matches between clinical problems and treatments. We conclude with a review of implications for policy and economic research.

For this substack, I’ve summed up my favorite parts of the paper, which draws upon psychology, economics, and history to evaluate changes in mental health treatment, policy, and outcomes.

Treatment

In 2019, 19.2% of American adults received mental health treatment, 15.8% used mental health medication, and 9.5% received psychotherapy.

In 2017, among Americans who received outpatient mental healthcare, 36% were treated by physicians, 36% by psychiatrists, 30% by non-physician mental health professionals (i.e. psychologists, social workers), and 30% by other non-physician health professionals (i.e. nurse practitioners).

Most mentally ill people are exclusively treated in outpatient settings, but 7.4% will be hospitalized at some point in their lives.

Stagnant Spending

In 1975, the US spent 1% of GDP on mental healthcare. In 2020, it was projected to spend 1.1%, only .1% more than 45 years ago. By contrast, overall healthcare spending grew from 6.5% to 19.7% in the same period.

Why did mental healthcare spending stagnate while overall healthcare spending tripled? The authors give four reasons:

Technological innovation (particularly capital-intensive devices and procedures) has been the main driver of ballooning healthcare costs, and there has been no equivalent in mental healthcare.

Mental healthcare patients have moved from more to less expensive treatments over time. Psychotherapy → prescription drugs. Mental institutions → community care. Seeing a psychiatrist → seeing a social worker. This reduces costs.

About two-thirds of mental healthcare is paid for by public funds, and public programs generally pay lower prices.

When institutionalization was a larger part of mental healthcare spending, the cost of housing, feeding, and looking after patients was considered “mental health spending.” Today people with serious mental illnesses are rarely institutionalized, so those costs aren’t considered mental health spending and get dispersed across non-profits, social services, and the criminal justice system.

Non-healthcare Costs

The authors calculated how many non-healthcare dollars are spent on the mentally ill:

The largest fraction is Social Security Disability Insurance ($31.2 billion), followed by jails and prisons ($13.5 billion) and policing ($12.3 billion).

Life Outcomes

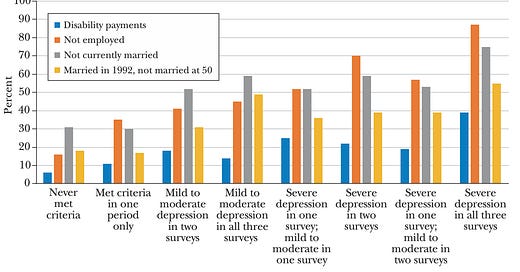

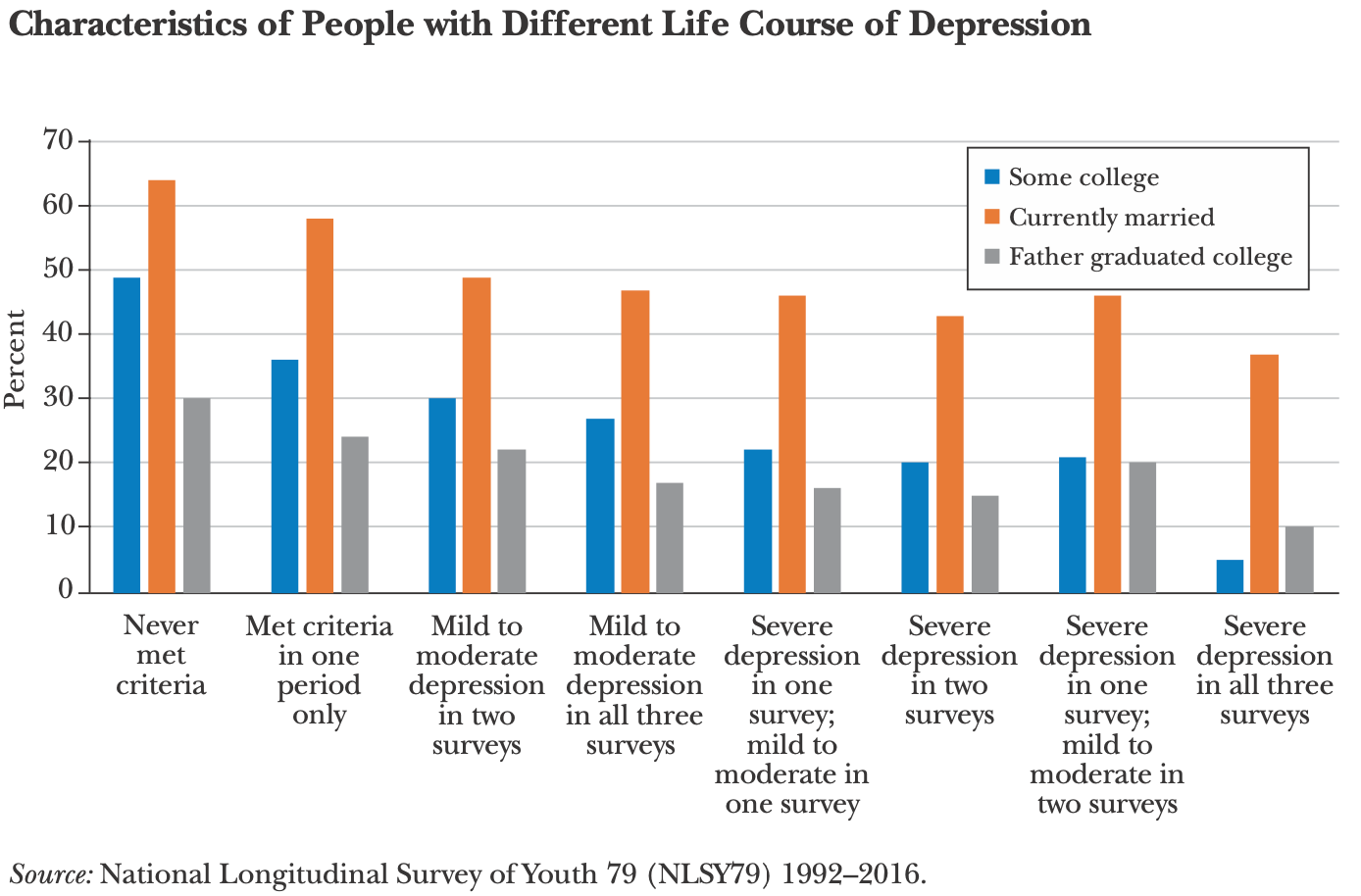

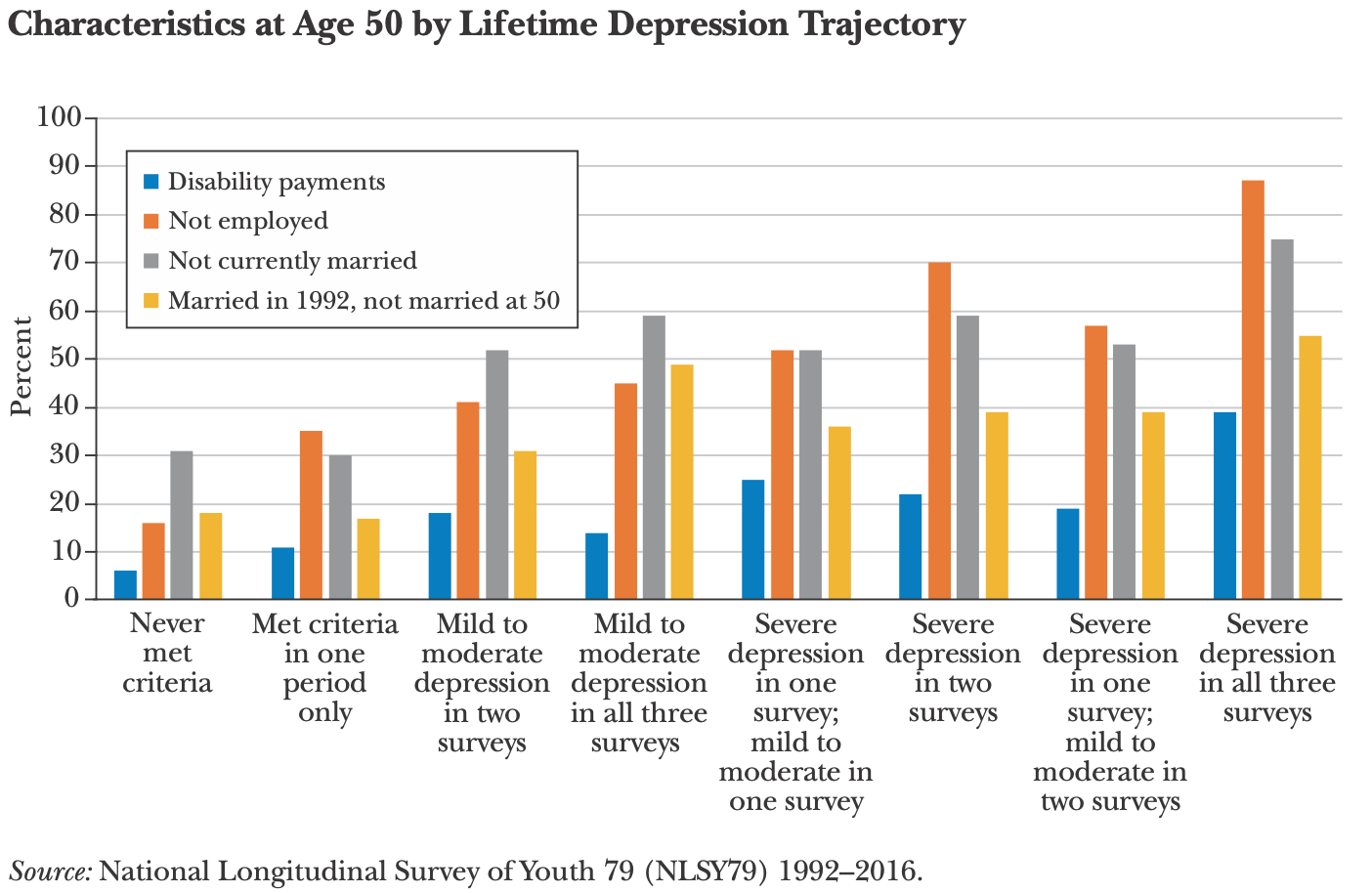

The authors wanted to look at the effect of mental illness on life outcomes, so they analyzed three waves of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79 (NLSY79). There’s a depression screening survey in each wave, and you can see huge differences between those who never met depression criteria and those who were severely depressed in all waves.

The differences are striking. Only 5% of those who were depressed in every wave attended college. At age 50, 40% were on disability, 88% were unemployed, 75% weren’t married, and 55% had divorced.

Facts about the Seriously Mentally Ill (i.e., Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder)

26% of people in jail and 14% in prisons have a serious mental illness.

23% of police shootings since 2015 involved someone with a serious mental illness.

Efforts to increase labor force participation for people with serious mental illnesses on disability payments have not been successful.

Less than 5% are currently institutionalized, while previously it was high as 29%.

Assertive Community Treatment teams are considered the “gold standard” of treatment for this group, and have been shown to reduce hospitalization.

The seriously mentally ill often have trouble getting housing and social services due to the complexity of policy designs and the debilitating nature of their illnesses. One study found that over a third of low-income women whose applications for Supplemental Security Income benefits were rejected met diagnostic screening criteria for serious mental illness.

The paper also includes some great policy recommendations. A key theme of theirs is that both overuse and underuse of mental health treatment and services are big problems, and finding policies that get more help to people who really need it while screening out those who don’t is a challenge:

Current policy choices have led to a misallocation of resources in the delivery of clinical services. Too few people with treatable mental health conditions, including those with serious illness, obtain care that could help them. This situation may arise, in part, because the decisions of people suffering from mental illness to seek care may not accurately reflect the likely value of such care to themselves and to others, as well as because of underinvestment in treatment capacity for the most serious conditions. At the same time, moral hazard associated with insurance coverage of mental health services may lead to overuse (or inappropriate use) of some services within this category, either to address problems of living that cause relatively little impairment or because the quality and nature of treatments are so variable. Both overuse and underuse reflect the fundamental difficulty of matching people and treatments in the face of great heterogeneity and uncertain diagnosis.

Read the full paper here.

Just posted this on /r/economics for you, idk maybe they will upvote it

https://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/140pme6/the_economics_of_mental_illness/